Christopher Bunting would have been 100 years old this week. He was, and remains a powerful influence on my life and, I imagine, on the lives of those of us lucky enough to have studied with him.

I met him first as a teenager when I performed at the Cambridge Competitive Music Festival. I played Kol Nidrei and Christopher was the adjudicator. Before that day, I had heard him broadcast and I knew he was an extraordinary cellist and teacher and, when he spoke to all of us taking part in that class, collectively and individually, we were taken to a different place of musical understanding and also of personal acknowledgement. I came to learn that Christopher always looked for the positives; it must have been a creed. What I didn’t know then, was that I was going to study with him.

When I went up to London for my first lesson, he began by telling me that anything worth doing well, was worth doing badly. This was striking as perfectionism, that killer of creativity, but nevertheless a driver of any musician, had a strong hold on me. First, I played to him, and he wrote notes – lots of them. I have my A4 notebook still, and recently went back to look at it and saw his comments about the good things going on, followed by technical observations, quirks needing to be ironed out, and then, he got down to the nitty-gritty.

This was the moment when I could see something different and empowering taking place. The technical construction process was underway and, as he talked, Christopher drew diagrams in blue ink with his beautiful fountain pen. He assumed a lot: I hadn’t heard anyone before talking in such an erudite way, explaining things scientifically, all the while assuming you understood. I was too shy to slow him down, and I think may have felt (then) that it wasn’t wise, or he may even be annoyed, but he simply wasn’t like that. The times were very different then, and our students now, feel a freedom to question whereas I didn’t – for a while.

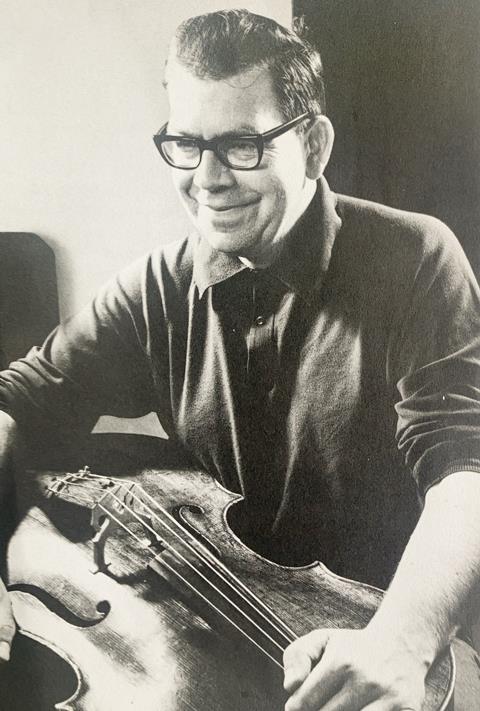

What was clear, was, that behind those glasses, I was aware of a person looking out while slightly hiding behind them. Most musicians are extroverted introverts and what was also evident, was a sense of humour, which was new to me in a teacher and has proven to be very empowering for my work as a teacher. He had a wry sense of humour.

In this first lesson he also talked about vocal music, of singers he was listening to, of observations. I left that day with instructions to make three arrangements for solo cello and returned with a Bach aria from the B Minor Mass, a song by Gerald Finzi and an aria from Verdi’s opera, Don Carlos. Of all the people I’ve learnt from, he talked about music the most and yet he is known as the great technical wizard, but he was clear that technique was always the route to expression.

Christopher took all his pupils incredibly seriously. He saw us as each having our own voice, which we would explore, develop over time, and use in many, varied ways. I discovered this when I was feeling I had to be able to play like Cellist A (something a lot of students did) I struggled with a patch in a Bach Prelude and announced that I couldn’t play in the same way as Cellist A, and he replied “No, you can’t. You will play this as You”

I think he knew we would also create our own paths and careers. Everyone does. He would attend our solo concerts if he could and talked so generously about other students and how things had gone for them at their performances, always positively and with great respect.

We were all learning with someone who knew that to teach was of great importance and a vital part of being a rounded musician. This was intrinsic to his nature, and he had had it modelled to him by Casals who believed that “To teach is to learn”.

I am so lucky to spend so much time teaching, thinking about the craft of cello playing, about music, and endlessly learning. Not for a nano-second was Christopher simply earning a living. He was doing what he had to do and, I imagine, he never stopped thinking.

We students came to expect, after the initial surprise of the magic taking place in our lives, pages and pages of photocopied exercises of his that became the books. Early on, when faced with some left-hand exercises, I asked myself how on earth I was going to be able to do them. The answer that came to me, was that I was going to have to visualise the anatomy of my hand: to travel inside it, see the joints, have a word with the soft tissue, not clamp my hand down to try to control (never worked) and hopefully, be able to pull it off.

The range of repertoire we learnt was wide and interesting too. From the standard concertos and sonatas to his arrangements of Ravel for thumb position, to the more left field. He introduced me to the Henze Serenade and the Martinu Sonatas and much more. When Christopher played Martinu, he revealed an east European soul made even more so by that powerful modern German cello he played it on.

One day, I was looking down at the floor, which was always interesting – a range of books, articles, objects and more, while Christopher wrote in my book. I noticed a huge manuscript. I was used to seeing manuscripts piled up on my father’s desk at home, prior to them being taken back into work, and asked Christopher what it was. He replied in a really sad voice “It’s my book – it’s just been rejected” He said a bit more about it and then I found myself piping up “My dad is a publisher, and started the music list at CUP, why not let me take it home?” The rest is history and my father, Michael Black, whom Christopher trusted and felt understood him intuitively, worked his legendary editorial skills and so there is now a vitally important record and vast, enriching resource from a musician and cellist of extreme importance.

I studied with Christopher for three years before I went to the RCM, where I had two more years, before a change of teacher. There came a time when I returned to that generous, understanding environment and at the same time, Fiona Murphy and I went to him for coaching as we formed a cello duo. This was a trigger to the creative imagination of our teacher, who very soon found us more repertoire, amongst it, music he owned and lent us and then, he arranged the Bourees from the third Suite for us to include in our performances.

When Christopher became wheelchair bound, Fiona and I used to go up to London with a lunch to cook for him. We would talk together in a wide-ranging way and hear about other students who were also in touch with him. One was regularly going round to his home to give him foot massages.

On one of these occasions, he talked about a student who flew over from Germany for lessons with him. He said he felt that his teaching was now at its best, because he couldn’t play. This was a lights-on moment for me. I think Fiona already knew this at a deep level, as she had studied with Jacqueline du Pre. The clarity for me though, was the realisation that of course this was true: because Christopher had no cello as an extension of his body and soul, he had to embody everything that was about being a cellist, through his senses, and his powerful intellect allied with his imagination.

There is so much to say about Christopher Bunting. There is an over-used word that does actually apply to him, and that is “genius”. He would be modest about this and maybe even a bit unnerved, but the experience was just that. Travelling with this guide, illuminating the way that he thought about, developed, experienced and processed endlessly, to share with those of us he taught. We were, and still are, his cello monks at the cello monastery he once said he wanted to create, and it is not over the top to say that his role as a master teacher was his musical-spiritual task on top of being a supremely fabulous cellist.

He created many passionate cellist – teachers and we are all proud of being assigned that role. He taught us to think, to grow, to trust ourselves when we were so young that some of us didn’t. We had to learn. He taught us to connect things, to love our music, new music, the cello, our musical life and to be creative and to constantly follow it through, whatever IT may be.

I have found that ageing and experience has brought so much perspective to so many aspects of a life in music. As I re-read obituaries about my/our teacher, I was struck by something else he said – that it’s what happens after the lesson that matters. It would be an act of honesty, to say that this can mean a day, a week, month, a year or longer, even decades for something to seat itself within.

We were, and are so, so lucky.